Computer-aided design (CAD) systems are proven tools used to design many of the physical objects we use every day. However, CAD software requires extensive expertise to master, and many tools have a high level of detail built into them, making them unsuitable for brainstorming and rapid prototyping.

In an effort to make design faster and more accessible to non-experts, researchers at MIT and elsewhere have developed an AI-powered robotic assembly system that can build physical objects simply by describing them in words.

Their system uses a generative AI model to build a 3D representation of an object’s geometry based on the user’s prompts. A second generative AI model then reasons about the object of interest and determines where various components should be placed depending on the object’s functionality and shape.

The system can automatically build objects from a series of prefabricated parts using robotic assembly. You can also iterate your design based on user feedback.

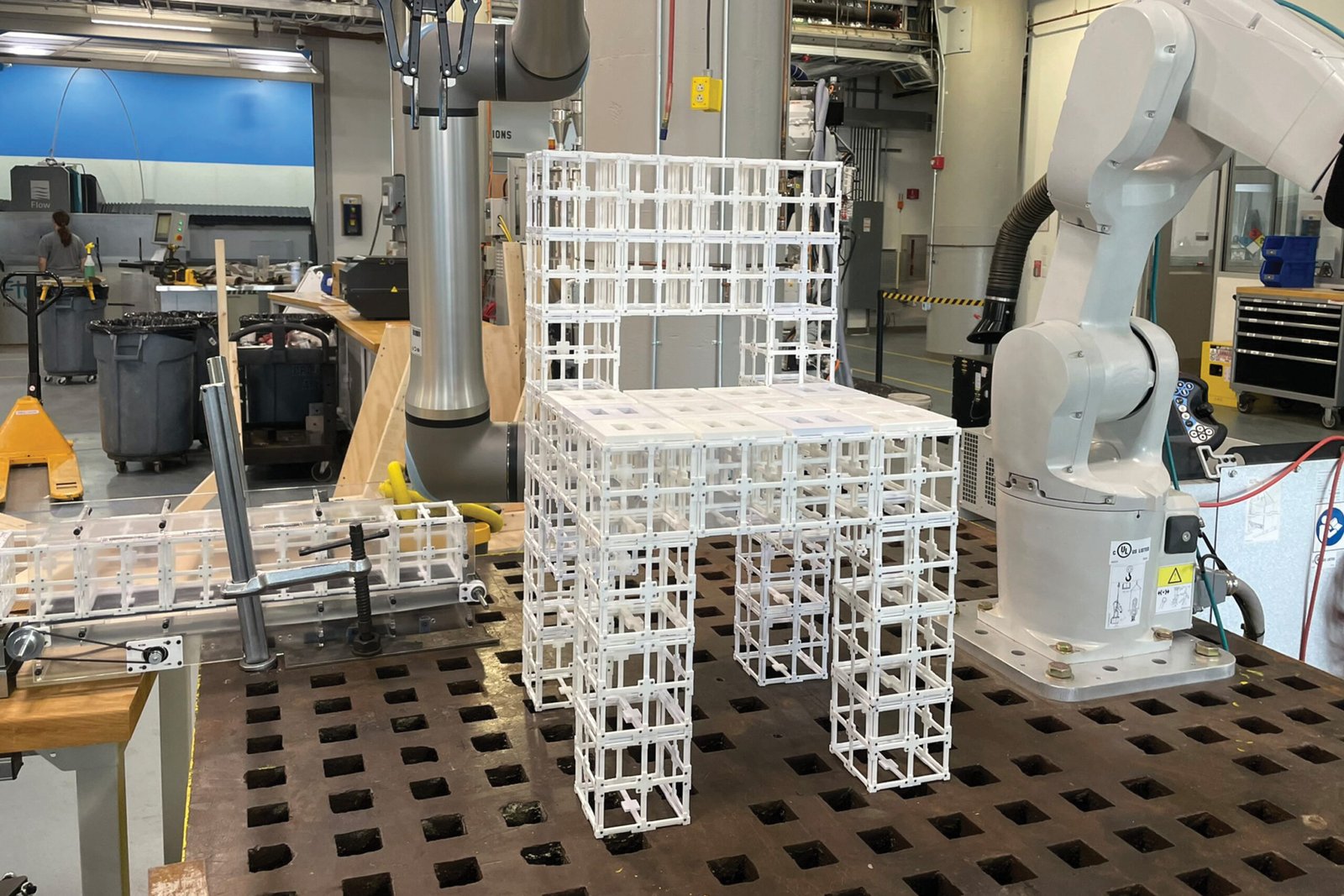

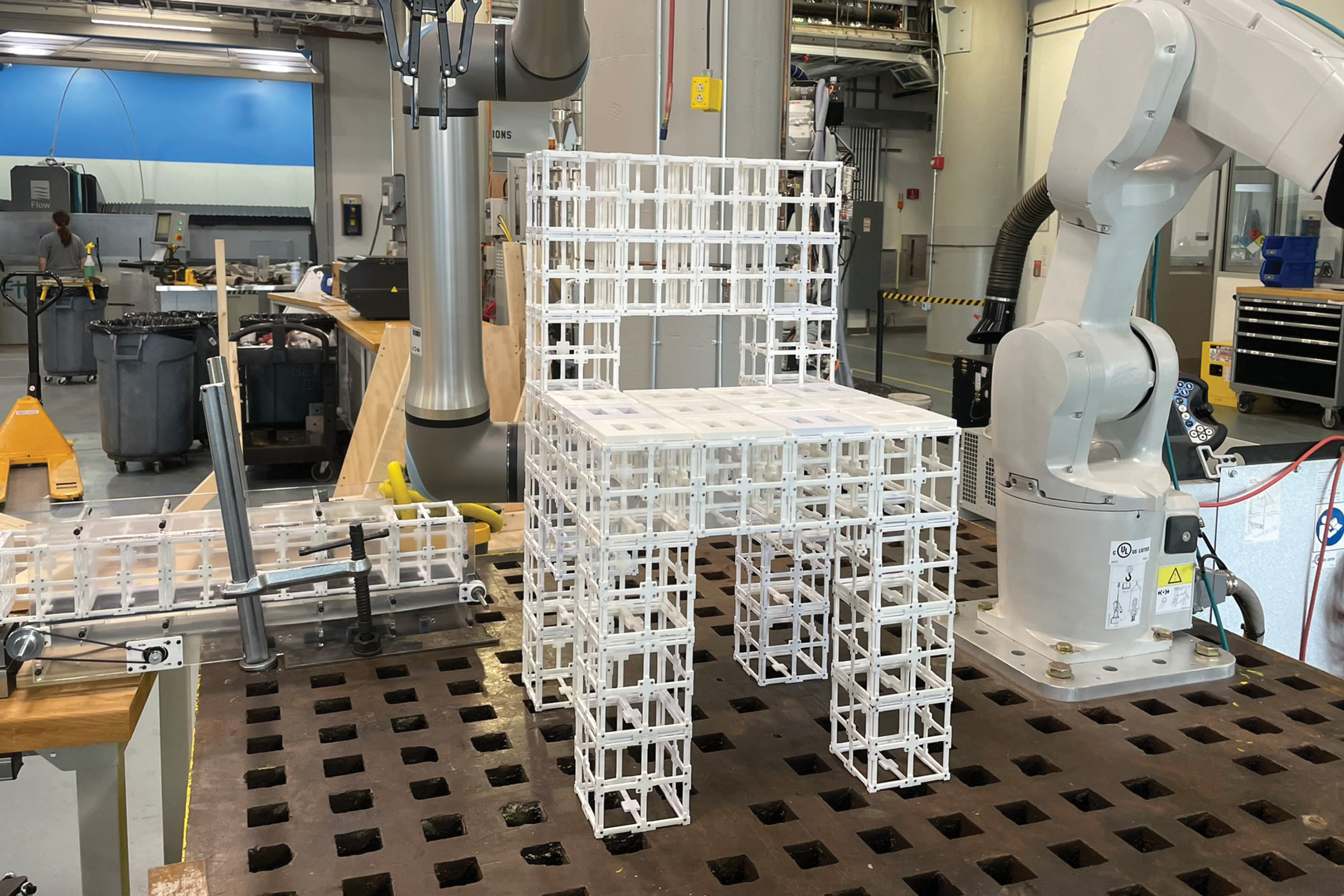

The researchers used this end-to-end system to manufacture furniture such as chairs and shelves from two types of prefabricated components. Components can be freely disassembled and reassembled, reducing the amount of waste generated during the manufacturing process.

They evaluated these designs through user research and found that more than 90 percent of participants preferred objects created with AI-driven systems compared to a variety of approaches.

Although this work is an early demonstration, the framework could be particularly useful for rapid prototyping of complex objects such as aerospace components and architectural objects. In the long term, it could be used in homes to manufacture furniture and other objects locally, without having to ship bulky products from central facilities.

“Sooner or later, we want to be able to communicate and talk to robots and AI systems in the same way that we interact with each other to build things together. Our system is the first step toward making that future a reality,” said lead author Alex Kyaw, a graduate student in the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) and Architecture.

Kyaw is joined on the paper by MIT architecture graduate student Richa Gupta. Faez Ahmed, associate professor of mechanical engineering. Professor Lawrence Sass, Head of the Computing Group, Department of Architecture. Lead author Randall Davis is an EECS professor and member of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). So do Google Deepmind and other members of Autodesk Research. This paper was recently presented at the Neural Information Processing Systems Conference.

Generate multi-component designs

Generative AI models are good at producing 3D representations, known as meshes, from text prompts, but most do not produce a uniform representation of an object’s geometry with the component-level detail needed to assemble a robot.

Dividing these meshes into components is difficult for models because component assignments depend on the geometry and functionality of the object and its parts.

Researchers tackled these challenges using the Vision Language Model (VLM), a powerful generative AI model pre-trained to understand images and text. They ask VLM to understand how two types of prefabricated parts fit together to form an object: structural components and panel components.

“There are many ways to place a panel on a physical object, but the robot needs to see the shape and reason about that shape to make decisions. The VLM allows the robot to do this by acting as both the robot’s eyes and brain,” Kyaw says.

The user starts by entering text into the system, perhaps by typing “Please make me a chair,” and giving it an AI-generated image of a chair.

VLM then makes inferences about the chair and decides where to place the panel component on the structural component, based on the features of the many sample objects it has seen so far. For example, the model can determine that the seat and backrest need panels to provide a surface for someone to lean back on.

This information is output as text such as “seat” and “backrest.” Each surface of the chair is numbered and that information is fed back to the VLM.

VLM then selects labels that correspond to the geometric parts of the chair that will accept the panels on the 3D mesh to complete the design.

Human-AI co-design

Users are kept in the loop throughout this process and can refine the design by giving the model new prompts, such as “Only use the back panel, not the seat.”

“The design space is very wide, so we narrow it down through user feedback. We think this is the best way to go because everyone has different tastes and it’s impossible to build the ideal model for everyone,” Kyaw says.

“The human-in-the-loop process allows users to interact with AI-generated designs and take ownership of the end result,” adds Gupta.

Once the 3D mesh is complete, a robotic assembly system uses prefabricated parts to construct the object. These reusable parts can be disassembled and reassembled into different configurations.

The researchers compared the results of their method with an algorithm that placed panels in all upward-facing horizontal planes and an algorithm that randomly placed the panels. In user research, over 90% of people preferred designs created with their system.

They also asked VLM to explain why it chose to install panels in these areas.

“We found that the visual language model can understand some of the functional aspects of the chair, such as tilting and sitting, and understand why we place panels on the seat and backrest. It doesn’t just randomly spit out these assignments,” Cho says.

In the future, the researchers hope to enhance the system to handle more complex and subtle user prompts, such as tables made of glass or metal. Additionally, we would like to incorporate additional prefabricated components such as gears, hinges, and other moving parts to give the object even more functionality.

“Our hope is to significantly lower the barrier to access to design tools. We have shown that generative AI and robotics can be used to turn ideas into physical objects in a fast, accessible, and sustainable way,” says Davis.