What can we learn about human intelligence by studying how machines “think”? If we can better understand the artificial intelligence systems that are becoming a more important part of our daily lives, can we better understand ourselves?

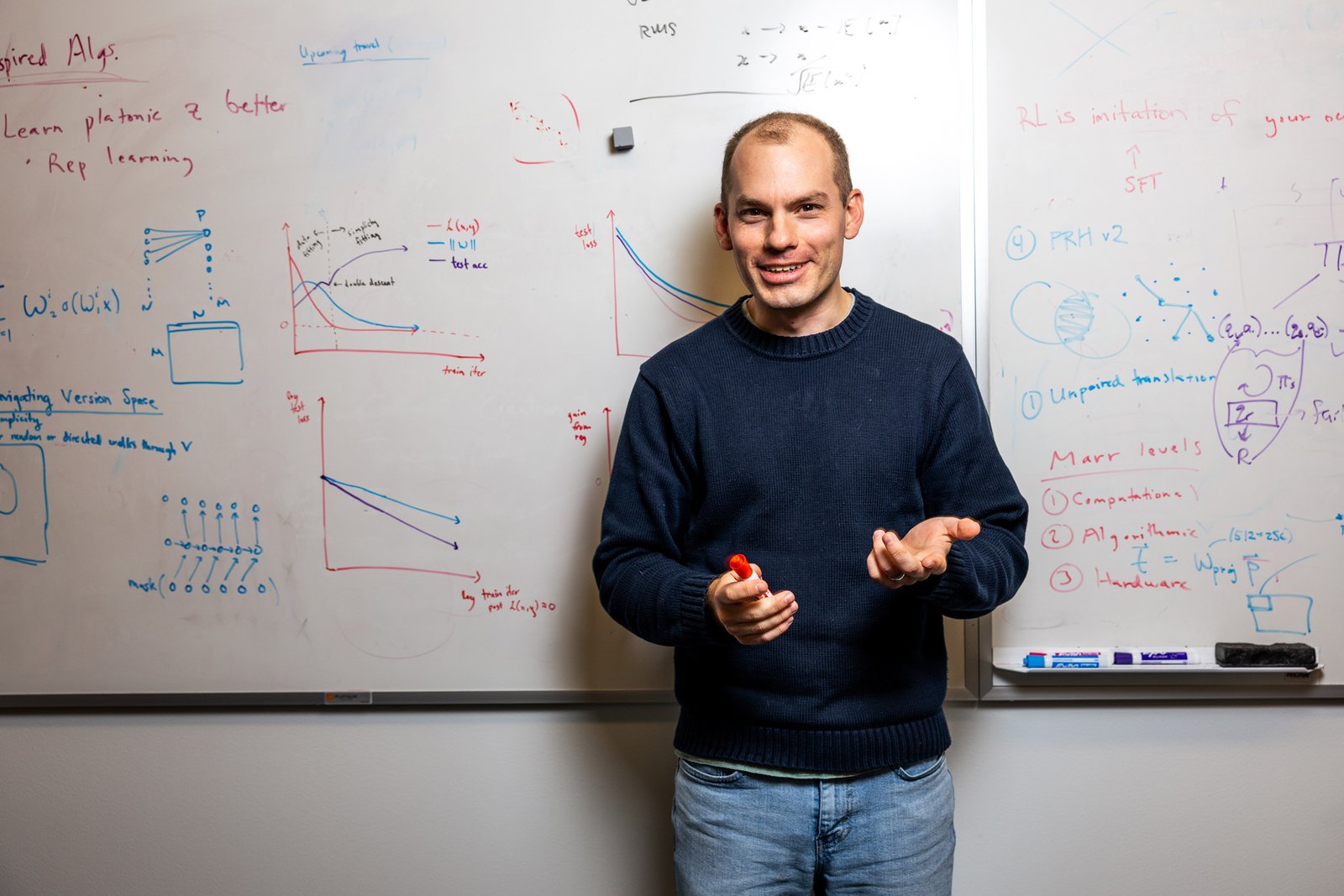

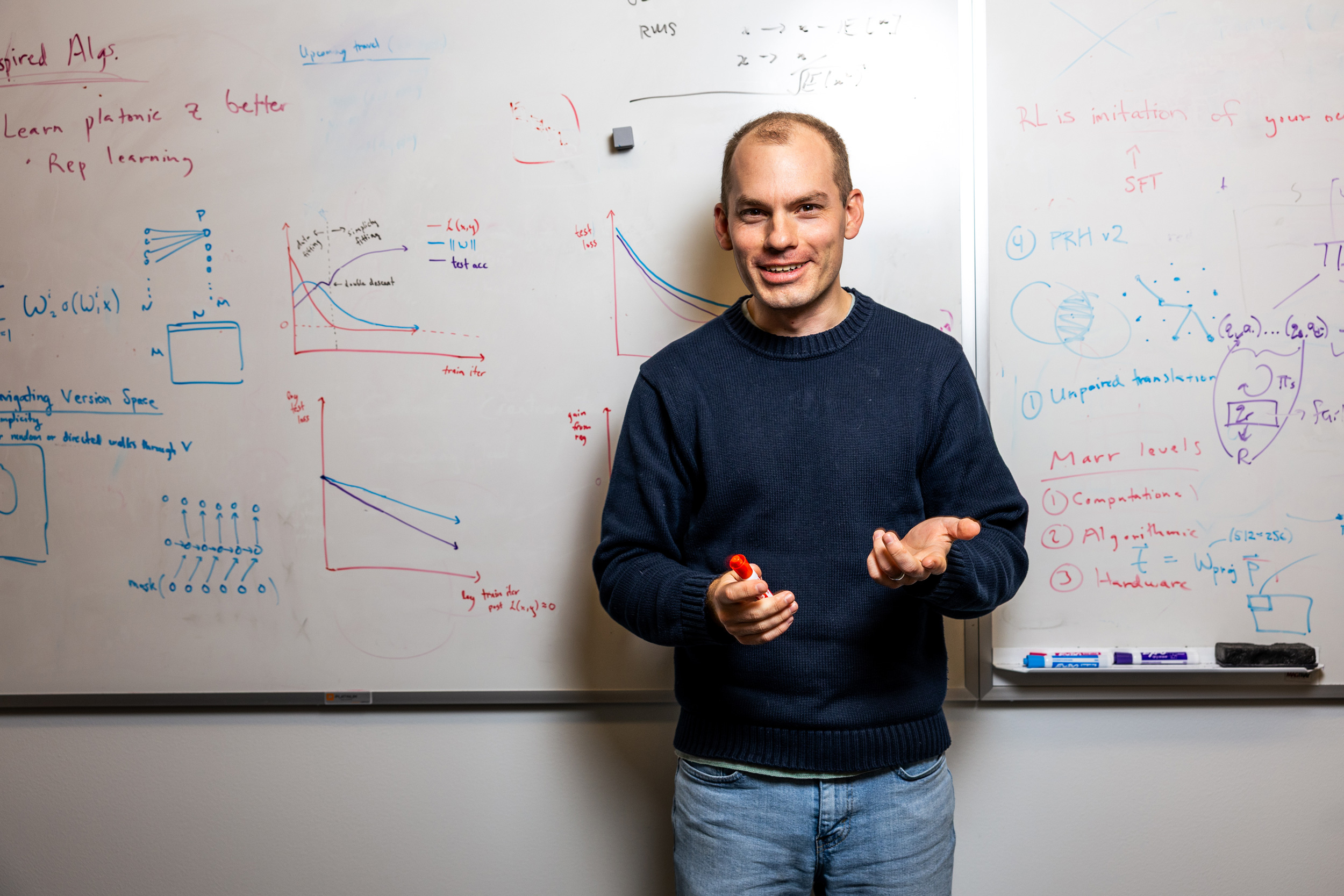

These questions may be deeply philosophical, but for Philippe Isola, finding the answers is as much a calculation as it is a thinking skill.

Isola is a newly tenured associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) who studies the fundamental mechanisms involved in human-like intelligence from a computational perspective.

Although understanding intelligence is a primary goal, his research primarily focuses on computer vision and machine learning. Isola is particularly interested in exploring how intelligence emerges in AI models, how these models learn how to represent the world around them, and what their “brains” share with the brains of their human creators.

“We believe that different types of intelligence have a lot in common, and we want to understand what they have in common. What do all animals, humans, and AI have in common?” said Isola, who is also a member of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Institute (CSAIL).

For Isola, a deeper scientific understanding of the intelligence of AI agents will help the world maximize its chances of safely and effectively integrating AI agents into society to benefit humanity.

ask a question

Isola began thinking deeply about scientific questions at an early age.

While growing up in San Francisco, he and his father frequently hiked along the Northern California coastline and camped around Point Reyes and in the foothills of Marin County.

He was fascinated by geological processes and often wondered how the natural world worked. At school, Isola was insatiably curious and was drawn to technical subjects like math and science, but there were no limits to what she wanted to learn.

Unsure of what to study as an undergraduate at Yale University, Isola dabbled in cognitive science until he discovered it.

“My interest before was in nature, how the world works, but then I realized that the brain is even more interesting and more complex than the formation of planets. Now I wanted to know what makes us tick,” he says.

During his first year, he began working in the lab of Brian Scholl, a professor of cognitive science and his soon-to-be mentor. Brian Scholl is a member of the Yale University Psychology Department. He remained in that lab throughout his undergraduate years.

After spending a gap year with some childhood friends at an indie video game company, Isola was ready to dive back into the complex world of the human brain. He enrolled in the Brain and Cognitive Sciences graduate program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“In graduate school, I felt like I had finally found my place. I had many great experiences at Yale and at other stages of my life, but when I got to MIT, I realized that this is a job that I truly love, and that these are people who think like me,” he says.

Isola credits his doctoral supervisor, Ted Adelson, and vision science professors John and Dorothy Wilson, as having a major influence on his future path. He was inspired by Adelson’s focus on understanding fundamental principles as well as pursuing new engineering benchmarks (formalized tests used to measure system performance).

Computational perspective

At MIT, Isola’s research moved toward computer science and artificial intelligence.

“I still love all these questions from cognitive science, but I felt like we could make even more progress on some of these questions if we approached them from a purely computational perspective,” he says.

His paper focused on perceptual grouping. This includes the mechanisms humans and machines use to organize separate parts of an image into a single, coherent object.

If machines can learn perceptual grouping on their own, AI systems could be able to recognize objects without human intervention. This type of self-supervised learning has applications in areas such as self-driving cars, medical imaging, robotics, and automatic language translation.

After graduating from MIT, Isola completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California, Berkeley, where he was able to expand his horizons by working in a lab focused solely on computer science.

“That experience made my work more impactful because I learned to balance an understanding of fundamental, abstract principles of intelligence with the pursuit of more concrete benchmarks,” Isola reflects.

At Berkeley, we developed an image-to-image transformation framework. This is an early form of generative AI model that can, for example, convert sketches into photographic images, or black and white photos into color photos.

He entered the academic job market and accepted a faculty position at MIT, but Isola deferred a year to work at a then-small startup called OpenAI.

“It was a nonprofit organization, and I liked its idealistic mission at the time. They were really good at reinforcement learning, and I thought that was an important topic to learn more about,” he says.

He enjoyed the scientific freedom of working in a lab, but after a year he was ready to return to MIT and start his own research group.

study human-like intelligence

I was immediately attracted to running a lab.

“I really like the early stages of an idea. I feel like it’s a kind of startup incubator where I can always do new things and learn new things,” he says.

Driven by an interest in cognitive science and a desire to understand the human brain, his group studies the fundamental computations involved in human-like intelligence in machines.

One of the main focuses is representational learning, the ability of humans and machines to represent and perceive the sensory world around them.

In recent research, he and his collaborators observed that different types of machine learning models, from LLMs to computer vision models to audio models, appear to represent the world in similar ways.

Although these models are designed to perform very different tasks, they have many similarities in architecture. And as they grow and are trained with more data, their internal structures become more similar.

This led Isola and his team to introduce the Platonic Representation Hypothesis (which takes its name from the Greek philosopher Plato), which claims that the representations learned by all these models converge on a shared underlying representation of reality.

“Language, images, sounds, these are all different shadows on the wall that you can infer from there that there is some underlying physical process, some kind of causal reality. If you train a model on all these different kinds of data, it should eventually converge on that model of the world,” Isola said.

A related area that his team is researching is self-supervised learning. This includes how an AI model can learn how to group related pixels in an image or words in a sentence without having labeled examples to learn from.

Because data is expensive and labels are limited, training a model using only labeled data can throttle the capabilities of an AI system. The goal of self-supervised learning is to develop models that can come up with accurate internal representations of the world on their own.

“The better you can represent the world, the easier it will be to solve problems later on,” he explains.

Isola’s research focus is on finding new and surprising things rather than building complex systems that outperform the latest machine learning benchmarks.

While this approach has had much success in uncovering innovative technologies and architectures, it means that the work may lack a concrete end goal, which can lead to challenges.

For example, if a lab is focused on looking for unexpected results, it can be difficult to keep teams aligned and funding flowing, he says.

“In a sense, we are always working in the dark. This is high-risk, high-reward work. Sometimes we discover new and surprising kernels of truth,” he says.

In addition to pursuing knowledge, Isola is passionate about passing it on to the next generation of scientists and engineers. One of his favorite courses he teaches is 6.7960 (Deep Learning). He and several other MIT faculty members launched the course four years ago.

The class has grown rapidly, starting with 30 students and growing to more than 700 this fall.

The popularity of AI means there is no shortage of interested students, but the speed of change in the field can make it difficult to separate the hype from the truly important advances.

“I tell my students that they have to take everything we say in class with a grain of salt. Maybe in a few years, we’ll be teaching something different. We’re really at the edge of knowledge in this course,” he says.

But Isola also reminds students that, despite all the hype surrounding the latest AI models, intelligent machines are much simpler than many people think.

“Many people believe that human ingenuity, creativity, and emotion can never be modeled. That may be true, but I think intelligence is fairly simple once you understand it,” he says.

Although his current research focuses on deep learning models, Isola remains fascinated by the complexity of the human brain and continues to collaborate with researchers studying cognitive science.

All the while, he remained fascinated by the beauty of the natural world, which sparked his initial interest in science.

Although he has less time for hobbies these days, Isola enjoys hiking and backpacking in the mountains and Cape Cod, skiing and kayaking, or finding scenic places to spend time when traveling for scientific conferences.

And while he looks forward to exploring new questions in the MIT lab, Isola can’t help but think about how the role of intelligent machines could change the direction of his research.

He believes that artificial general intelligence (AGI), or machines that will be able to learn and apply knowledge in the same way as humans, is not far away.

“I don’t think AI will do everything for us and we’ll go to the beach and enjoy life. I think there will be this kind of coexistence between smart machines and humans who still have a lot of agency and control. Now I’m thinking about some interesting questions and applications when that happens. How can we help the world in this post-AGI future? I don’t have an answer yet, but it’s on my mind,” he says.