In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, antibiotics can become double-edged swords. A wide range of drugs often prescribed for intestinal flare-ups can kill microorganisms that are useful along with harmful microorganisms, and sometimes the symptoms can worsen. When fighting intestinal inflammation, you don’t always want to bring a sledgehammer to the knife fight.

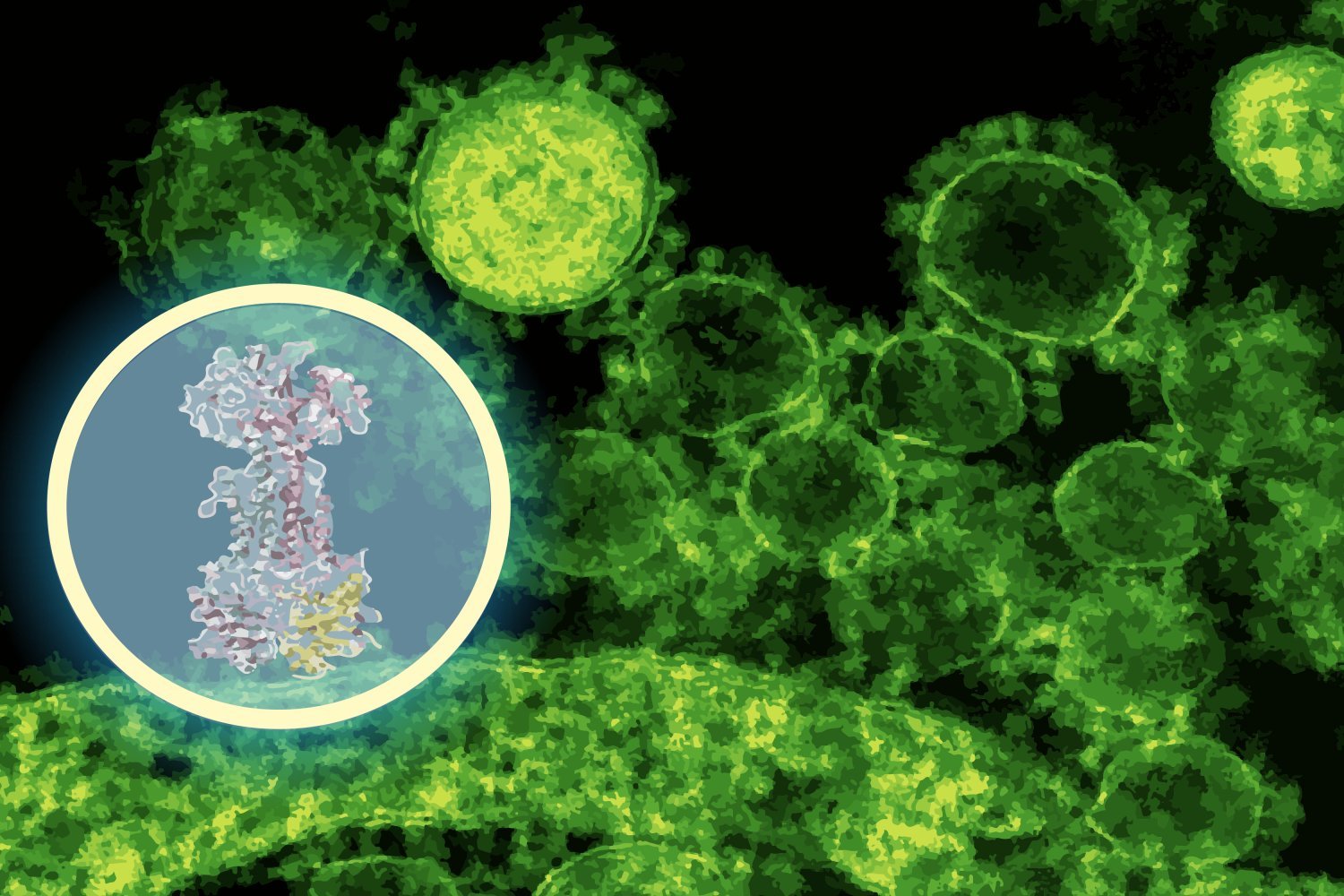

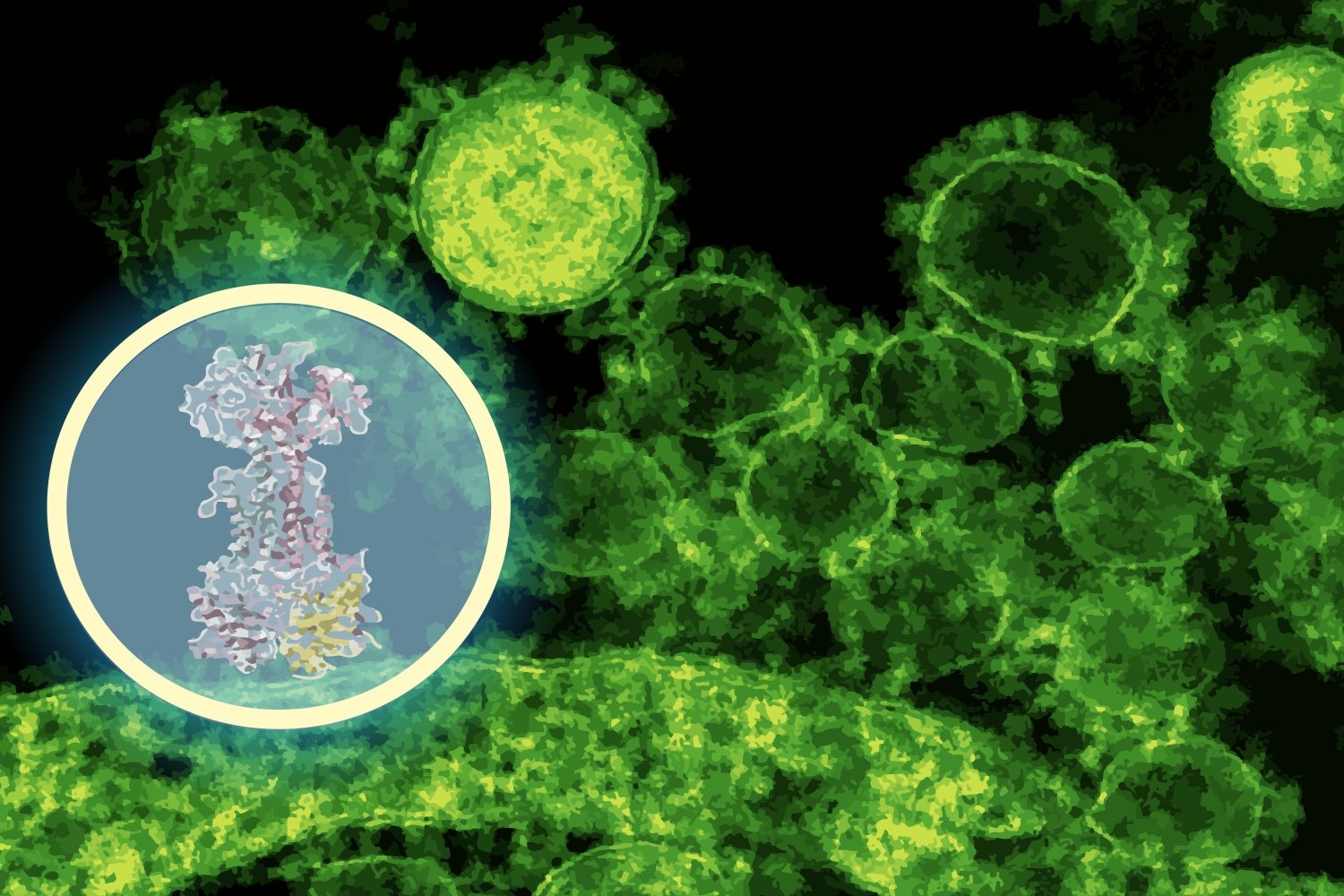

Researchers at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Institute (CSAIL) and McMaster University have identified new compounds that take a more targeted approach. A molecule called enterolin suppresses groups of bacteria associated with Crohn’s disease, leaving the remainder of the remaining microbiota largely intact. Using generative AI models, the team mapped the mechanisms of compounds. This is a process that usually takes years, but here it has been accelerated to several months.

“The discovery speaks to a central challenge in antibiotic development,” says Jon Stokes, senior author of a new work paper, an assistant professor of biochemistry and biomedical sciences at McMaster and researcher at MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Clinic, a researcher for machine learning in health. “The problem was that, rather than finding molecules that kill bacteria in the dish, we were able to do that for a long time. Understanding what these molecules actually do within the bacteria. Without that detailed understanding, we cannot develop these early stage antibiotics into safe and effective treatments for patients.”

Enterolin is an advancement towards precision antibiotics. It is a treatment designed to knock out only the bacteria that cause problems. In mouse models of clone-like inflammation, drugs have gone to zero E. colia living intestinal bacteria that can exacerbate flares, leaving most other microbial residents untouched. Mice received enterolin recovered faster than those treated with the common antibiotic vancomycin, and maintained a healthier microbiota.

When the mechanism of action of a drug is fixed, molecular targets that bind within bacterial cells usually require years of laborious experimentation. Stokes’Lab discovered enterolin using a high-throughput screening approach, but determining its target was a bottleneck. Here, the team turned to Diffdock, a generative AI model developed in CSAil by MIT PhD student Gabriele Corso and MIT professor Regina Barzilay.

Diffdock was designed to predict how small molecules fit into protein binding pockets. This is a notorious problem in structural biology. Traditional docking algorithms use scoring rules to search for possible orientations, often producing raucous results. Instead, Diffdock docks as a problem of stochastic reasoning. The diffusion model repeatedly refines the guesswork until it converges to the most likely binding mode.

“In just a few minutes, the model predicted that enterolin would bind to a protein complex called LolCDE, which is essential for transporting lipoproteins from specific bacterial species,” says Barzilay, co-leading Jameel Clinic. “It was a very specific lead. It’s something that can guide the experiment rather than swapping it.”

Stokes’ group then tested the predictions. Using diffdock prediction as an experimental GPS, they first evolved the enterolin resistance mutants E. coli The lab revealed that DNA changes in the mutant were mapped to LOLCDE. They also performed RNA sequencing to see which bacterial genes were turned on or off when exposed to the drug, and used CRISPR to selectively knock down the expression of the expected target. All of these laboratory experiments revealed confusion in pathways associated with lipoprotein transport.

“When you see wet love data pointing to the same mechanism as the computational model, that’s when you start to believe you understand something,” Stokes says.

For Barzilay, the project highlights a change in the way AI is used in life sciences. “Many use of AI in drug discovery has been to search the chemical space and identify new active molecules,” she says. “What we’re showing here is that AI can provide a mechanical explanation, which is important for moving molecules through the development pipeline.”

The distinction is important because, in many cases, the study of action mechanisms is a major rate-limiting step in drug development. A traditional approach can take 18 months to 2 years or more, and costs millions of dollars. In this case, the MIT-MCMaster team reduced their timeline to about six months at a small cost.

Enterolin is still in its early stages of development, but translation is already underway. Stokes spin-out company Stoked Bio is licensed for the compound and optimizes its properties for potential human use. Early studies also investigated the derivatives of molecules against other resistant pathogens. Klebsiella pneumoniae. If everything goes well, clinical trials could begin in the next few years.

Researchers also see a broader meaning. Narrow spectral antibiotics have long been sought as a way to treat infections without secondary damage to the microbiota, but have been difficult to discover and verify. AI tools like Diffdock can make the process more practical and quickly enable new generations of targeted antibiotics.

For cloned patients and other patients with inflammatory bowel conditions, the prospect of drugs that reduce symptoms without instability in the microbiome can mean meaningful improvements in quality of life. And in a larger picture, precision antibiotics may help tackle the increasing threat of antibiotic resistance.

“What excites me is the idea that not only this compound, but the right combination of AI, human intuition and laboratory experiments can help you start thinking about how to make action mechanisms faster,” Stokes says. “It could change the way we approach drug discovery, not just because of clones, but because of many diseases.”

“One of our biggest challenges to health is the increase in antibacterial resistant bacteria that avoid even our best antibiotics,” said Yves Brun, a well-known professor emeritus at Indiana University Bloomington at the University of Montreal, who was not involved in the paper. “AI is becoming an important tool in the fight against these bacteria. This study uses a powerful and elegant combination of AI methods to determine the mechanisms of action of new antibiotic candidates, a critical step in potential development as a therapeutic agent.”

Corso, Barzilay, and Stokes wrote McMaster researchers Denise B. Catacutan, Vian Tran, Jeremie Alexander, Yeganeh Yousefi, Megan Tu, Stewart Mclellan, and Dominique Tertigas, as well as Jakob Magolan, Michaal Sureette, Eric Brown, and Brian Coombes. Their research was supported in part by the Weston Family Foundation. David Brayley Center for Antibiotic Discovery. Canadian Institute of Health. Canada’s Natural Science and Engineering Research Council. M. and M. Heersink; Institute of Health Research, Canada. Ontario Graduate Scholarship Award. Jameel Clinic; and the US Defense Threat Reduction Agency discovers medical measures against new threat programs.

The researchers posted sequence data to a public repository and publicly released Diffdock-L code on GitHub.