Since its invention in 1983, 3D printing has come a long way with Chuck Hull, a technology that uses ultraviolet lasers to solidify liquid resins into solid objects. For decades, 3D printers have evolved from experimental curiosity to tools that can produce everything from custom prostheses to complex food designs, architectural models, and even functional human organs.

But as technology matures, its environmental footprint is becoming increasingly difficult to put aside. The majority of consumer and industrial 3D printing still relies on oil-based plastic filaments. And while there are “green more” alternatives made from biodegradable or recycled materials, they have serious trade-offs. These environmentally friendly filaments tend to become brittle under stress, making them inappropriate for structural applications and load-bearing parts.

This trade-off between sustainability and mechanical performance allowed researchers at MIT’s Computer Science and Artiten Intelligence Institute (CSAIL) and the Hasso Plattner Institute to ask.

Their answer is SustainAprint, a new software and hardware toolkit designed to allow users to strategically combine powerful and weak filaments to make the most of both worlds. Instead of printing the entire object with high performance plastic, the system analyzes the model via finite element analysis simulations to predict where the object is most likely to experience stress, and only strengthen those zones with more powerful materials. The rest of the section can be printed using weak green filaments, reducing plastic use while maintaining structural integrity.

“Our hope is that it can be used one day in industrial and distributed manufacturing settings. Local materials inventory may differ in quality and configuration.” “In these contexts, test toolkits can help ensure the reliability of available filaments, but software enhancement strategies can reduce overall material consumption without sacrificing functionality.”

For their experiments, the team used Polymaker’s Polyterra PLA as environmentally friendly filament and Ultimaker’s standard or tough PLA for reinforcement. They used a 20% reinforcement threshold and showed that even small amounts of strong plastic can go a long way. Using this ratio, SustainAprint was able to recover up to 70% of the strength of an object fully printed with high performance plastic.

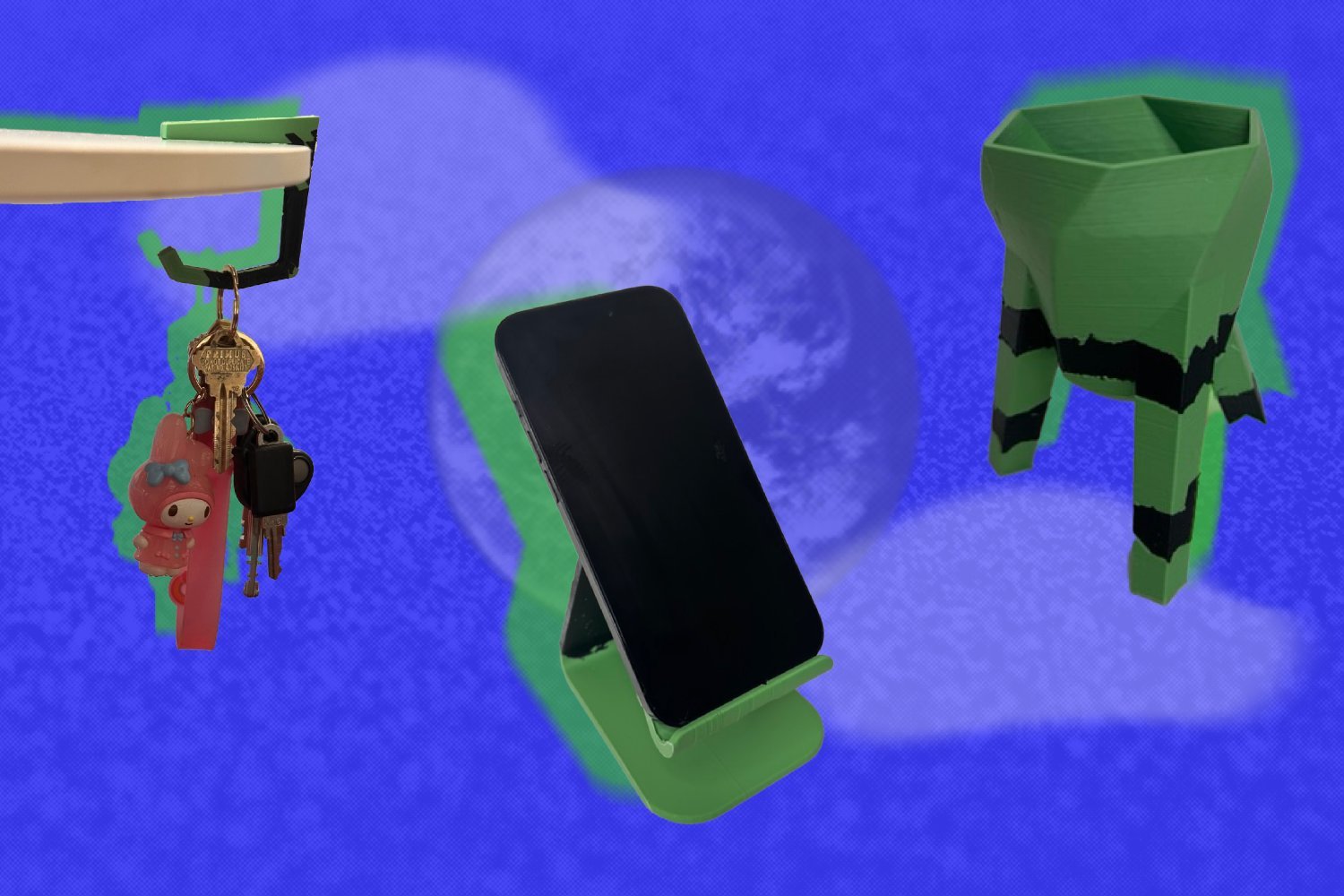

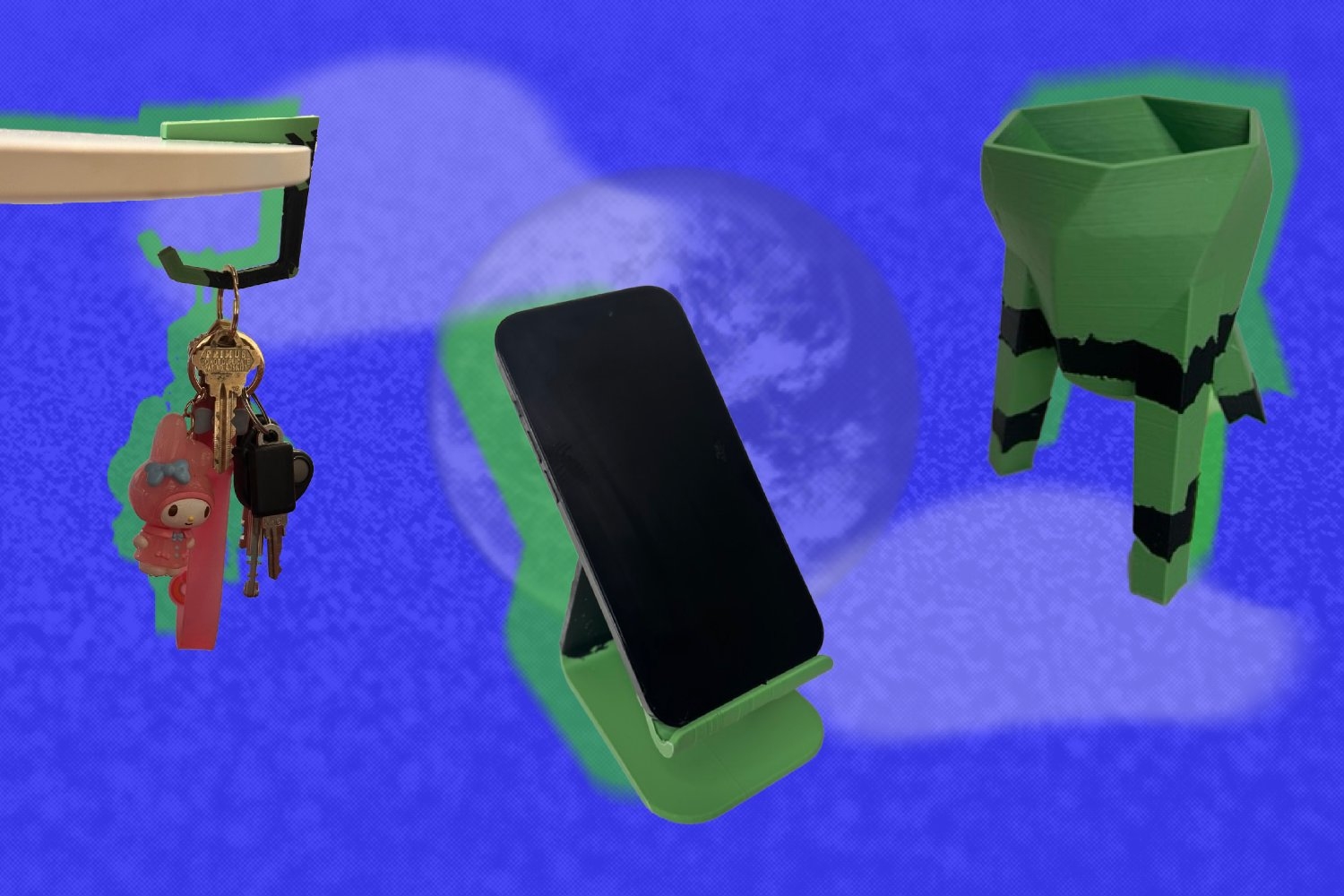

They printed a number of objects, ranging from simple mechanical shapes such as rings and beams to more functional household items such as headphone stands, wall hooks and plant pots. Each object was printed in three ways: At one point, use only environmentally friendly filaments, only strong PLAs, and use hybrid sustainer print configurations. The printed parts were then mechanically tested by pulling, bending, or breaking to measure how much force each configuration could withstand.

In many cases, the hybrid print was lifted up like almost the full-power version. For example, in one test, which includes dome-like shapes, the hybrid version outperformed the completely tough plastic-printed version. The team believes this could be due to the ability to distribute stress more evenly in the enhanced version.

“This shows that strategic mixing of materials at certain geometry and load conditions can actually be better than a single homogeneous material,” says Perroni-Scharf. “It reminds us that real-world mechanical behavior is full of complexity, especially in 3D printing, where interlayer adhesion and toolpath determination can affect performance in unexpected ways.”

Essential green printing machine

SustainAprint starts by allowing 3D models to be uploaded to a custom interface. By selecting the fixed regions and regions where the force is applied, the software uses an approach called “finite element analysis” to simulate how an object deforms under stress. Next, create a map showing the pressure distribution within the structure, highlight areas under compression or tension, and apply heuristics to divide the object into two categories. These are categories that require reinforcement and those that do not.

Recognizing the need for accessible and low-cost testing, the team also developed a DIY testing toolkit that will help users assess their strength before printing. The kit has a 3D printable device with modules for measuring both tensile strength. Users can pair their devices with popular items such as pull-up bars and digital scales to get rough and reliable performance metrics. The team benchmarked results for manufacturers’ data and found that even for filaments undergoing multiple recycle cycles, the measurements were consistently within one standard deviation.

Although the current system is designed for double-emission printers, researchers believe manual filament replacement and calibration can also be adapted to single-extractor setups. In the current format, the system simplifies the modeling process by allowing only one force and one fixed boundary per simulation. While this covers a wide range of common use cases, the team is looking at future work expanding the software to support more complex and dynamic load conditions. The team also sees the possibility of using AI to infer the intended use of an object based on its shape. This allows for fully automated stress modeling without manual input of forces or boundaries.

3D free

Researchers plan to release an open source for SustainaPrint, making both the software and the testing toolkit available for public use and modification. Another initiative they are aiming to bring back to life in the future: education. “In the classroom, Sustainaprint is not just a tool, it’s a way to teach students about material science, structural engineering and sustainable design in one project,” says Perroni-Schrach. “We’re turning these abstract concepts into concrete.”

Sustainability concerns are heightened as 3D printing is built into how everything is manufactured and prototyped, from consumer goods to emergency equipment. With tools like Sustainaprint, these concerns don’t have to come at the expense of performance. Instead, they can become part of the design process: they are embedded in the very geometry of what we make.

Co-author Patrick Baudisch, professor at the Hasso Plattner Institute, said, “The project addresses important questions. What is the point of collecting materials for recycling purposes?

Perroni-Scharf and Baudisch wrote a paper with CSAIL Research Assistant Jennifer Xiao. MIT Master’s student Cole Paulin ’24; Master’s Ray Wang SM ’25 and PhD student Ticha Sethapakdi SM ’19 (both CSAIL members). Muhammad Abdullah, a student at Hasso Plattner Institute PhD; Associate Professor Stefanie Mueller, lead of the Human Computer Interaction Engineering Group at Csail.

The researcher’s work was supported by the design of the Sustainability Grant from the design of the Sustainability MIT-HPI Research Program. Their work will be presented at the ACM symposium on user interface software and technology in September.