Mc Escher’s artwork is an entrance into a world of optical fantasies that go against depth, featuring “impossible objects” that break the laws of physics with complex geometry. What you perceive his illustrations as dependent on your perspective – for example, a person who appears to be walking upstairs may be descending stairs when he tilts his head to the side.

Computer graphics scientists and designers can replicate these fantasies in 3D, but can only be recreated by bending or cutting the actual shape and placing it at a specific angle. However, this workaround has its drawbacks. Changing the smoothness of the structure and lighting reveals that it is not actually an optical fantasy. This means that geometry problems cannot be solved accurately.

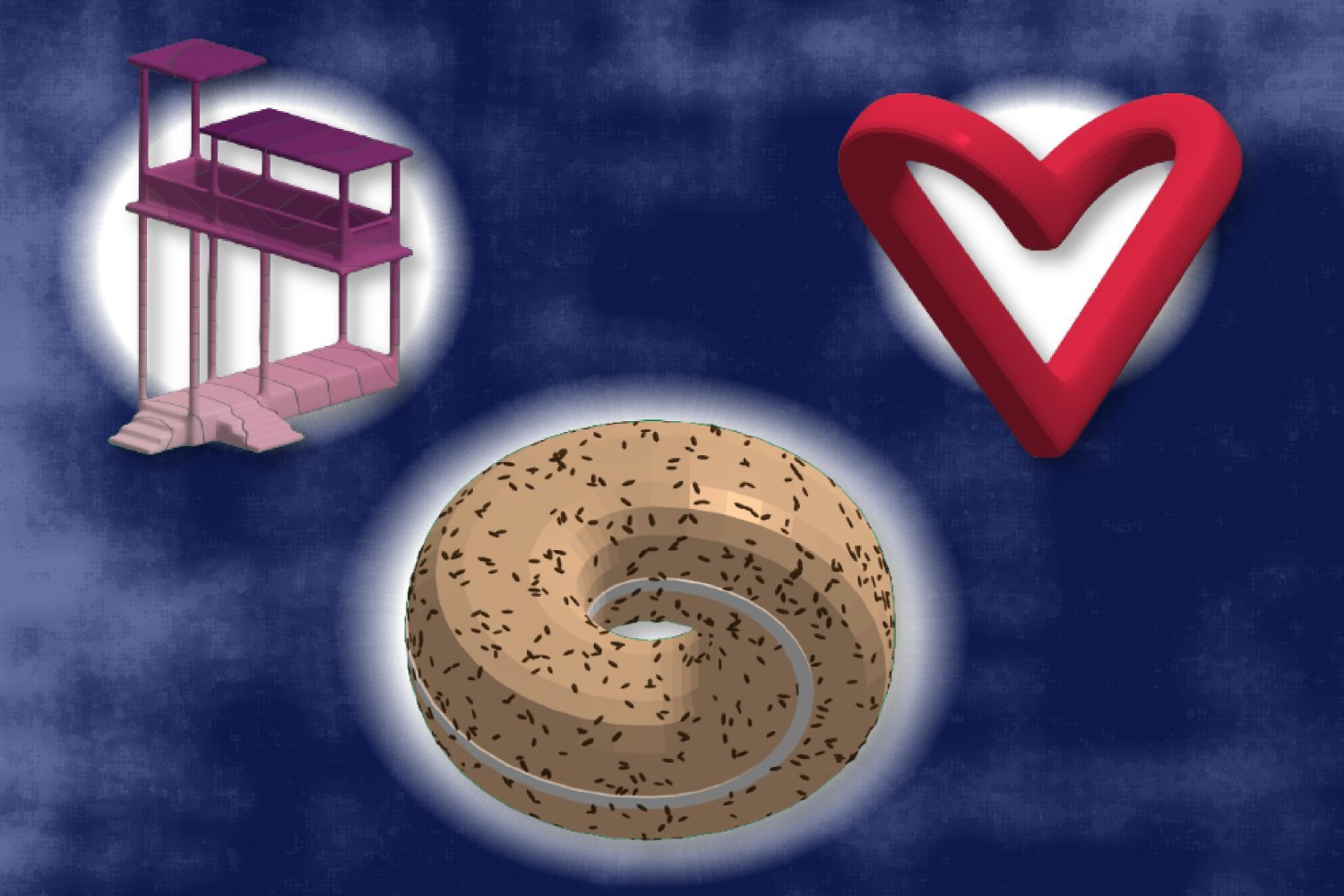

Researchers at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Institute (CSAIL) have developed a unique approach to representing “impossible” objects in a more versatile way. Their “Meschers” tool transforms images and 3D models into 2.5-dimensional structures, creating Escher-like depictions of windows, buildings, and even donuts. This approach helps users re-adjust, smooth and study their own shapes while maintaining their optical illusion.

This tool helps geometry researchers calculate the distance between two points on a curved, impossible surface (“survey measurement”) and simulate the way heat dissipates it (“heat diffusion”). It also helps artists and computer graphics scientists create physical designs in multiple dimensions.

Ana Dodik, a lead author and a doctoral student at MIT, aims to design computer graphics tools that are not limited to real-life reproduction. “We used Meschers to unlock the shapes of our new classes for artists to work on computers,” she says. “They were also able to help scientists realize that objects become truly impossible.”

Dodik and her colleagues will be presenting their papers at the Siggraph meeting in August.

Making impossible objects possible

It is not possible to replicate impossible objects completely in 3D. Although those components often appear plausible, these parts do not adhere properly when assembled in 3D. However, as CSAil researchers have learned, what can be computationally mimicked is the process of how these shapes are perceived.

For example, take a penrose triangle. The entire object is physically impossible because it doesn’t “sum” the depth, but it can recognize the actual 3D shapes within it (like three L-shaped corners). These small areas can be realized in 3D, a property called “local consistency,” but when you try to assemble them together, they do not form a globally consistent shape.

Mescher approaches the locally consistent region of the model and stitches Escher-style structures together without being globally consistent. Behind the scenes, the mesher represents impossible objects as if they knew the x and y coordinates in the image, representing the difference in z coordinates (depth) between adjacent pixels. This tool uses these differences in depth to indirectly infer impossible objects.

Many uses of meshers

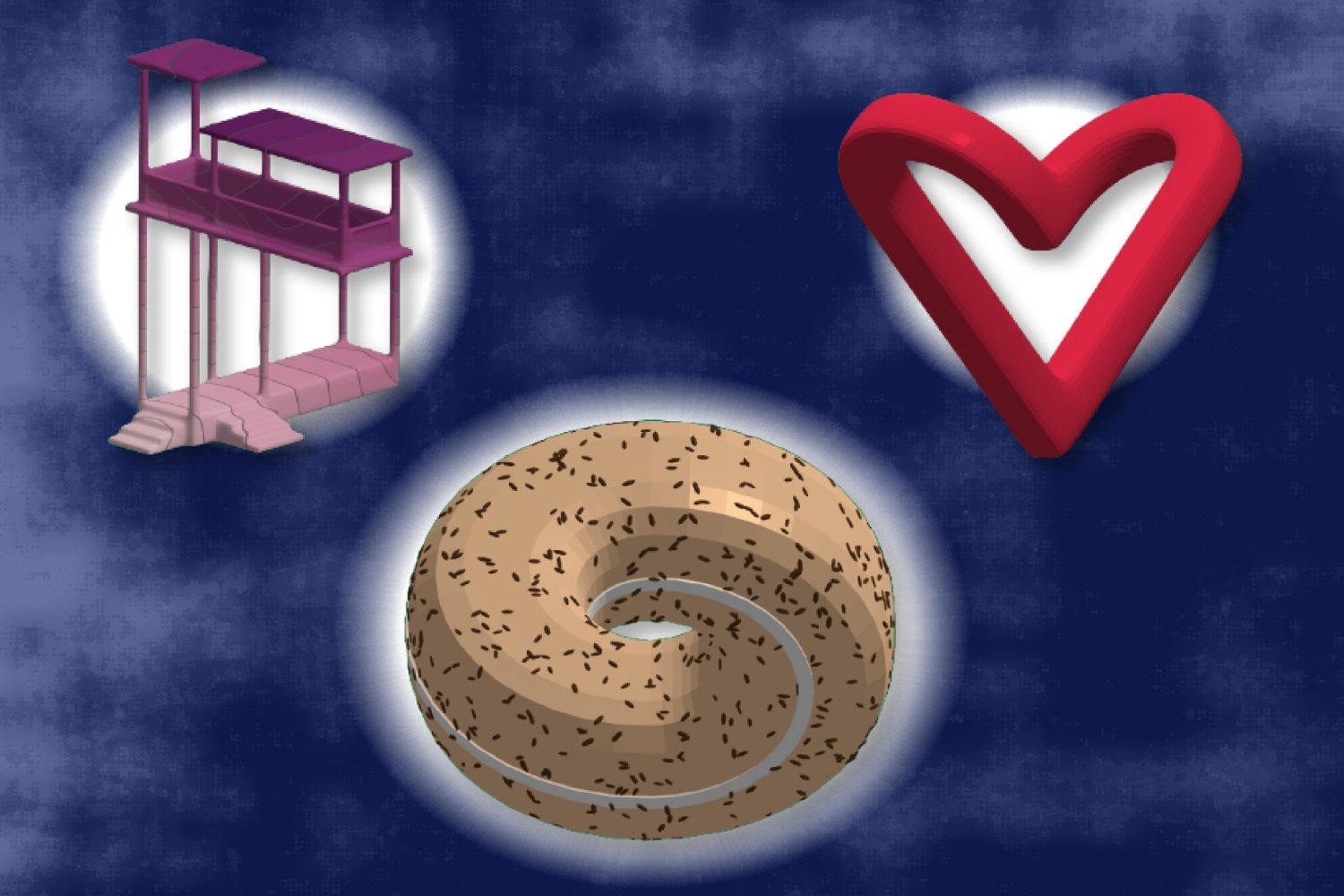

In addition to rendering impossible objects, the mesher can split the structure into smaller shapes for more accurate geometry calculations and smoothing operations. This process allowed researchers to reduce visual defects of impossible shapes, such as the thinned red heart outline.

Researchers also tested the tool on “Interibagel,” where bagels are shaded in a physically impossible way. Meschers helped Dodik and her colleagues simulate thermal diffusion and calculate the geodetic distance between different points in the model.

“Imagine you’re ant crossing this bagel. For example, you want to know how long it takes,” Dodik says. “In the same way, our tools help mathematicians to closely analyze the geometry underlying impossible forms, just like how they study the real world.”

Like magicians, this tool can create optical illusions from otherwise practical objects, making it easier for computer graphics artists to create objects that are impossible. You can also use the “Reverse Render” tool to convert drawings and images of impossible objects into high-dimensional designs.

“Meschers shows that computer graphics tools need not be constrained by rules of physical reality,” said Justin Solomon, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and senior author, leader of the CSAIL Geometry Data Processing Group. “Incredibly, artists using Mesher can infer shapes that would never be seen in the real world.”

Meschers can also help computer graphics artists fine-tune the shading of their works, yet still maintaining their optical illusions. This versatility allows creatives to paint a wide range of scenes (such as sunrise and sunset) as shown by changing the lighting of art to re-rated dog models on skateboards.

Despite its versatility, Mesher is just the beginning of Dodik and her colleagues. The team is considering designing an interface to make the tools easier to use while building more elaborate scenes. We are also working with Perception Scientists to see how computer graphics tools can be used more widely.

Dodik and Solomon wrote the paper along with Csail Affiliates Isabella Yu ’24 and SM ’25. PhD Students Kartik Chandra SM ’23; MIT Professors Jonathan Lagan Kelly and Joshua Tenenbaum. Vincent Sitzmann, Assistant Professor, MIT.

Their work includes the MIT Presidential Fellowship, Mathworks Fellowship, The Hertz Foundation, The Us National Science Foundation, Schmidt Sciences AI2050 Fellowship, US Army Laboratory, US Air Force Science Laboratory, SystemsThateLALN@CSAIL INIAT, Google, Google, Google, systes Adobe Systems, Singapore Defense Science and Technology Agency, and US Intelligence Advanced Research Project Activities.