In the office of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), soft robot hands carefully curl their fingers to grab a small object. The interesting part is not the mechanical design or embedded sensors. In fact, there’s nothing in your hand. Instead, the entire system relies on a single camera that monitors the movement of the robot and uses its visual data to control it.

This feature comes from a new system developed by CSAIL Scientists and provides a different perspective on robot control. Rather than using hand-designed models or complex sensor arrays, robots can learn how their body responds to control commands through their vision alone. This approach, called Neural Jacobian Fields (NJF), gives robots physical self-awareness. An open access paper about the work has been released Nature June 25th.

“This work illustrates the transition from programming robots to robot education,” said Sizhe Lester Li, MIT PhD student, CSAIL affiliate and researcher, Principal Investigator of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. “Today, many robotic tasks require extensive engineering and coding. They will allow robots to learn how to autonomously achieve their goals, assuming that they will show them what to do in the future.”

Motivation comes from simple but powerful reconstruction. The main barrier to affordable flexible robotics is not hardware. This is a control of functionality that can be achieved in multiple ways. Traditional robots are built to be stiff and sensor-rich, making it easier to build digital twins, the precise mathematical replica used for control. However, when the robot is soft, deformed or irregularly shaped, those assumptions fall apart. Rather than matching the model, the NJF gives the robot the ability to flip the script and learn its internal model from observation.

Look and learn

This separation of modeling and hardware design can greatly expand the design space for robotics. In soft, bio-inspired robots, designers often embed sensors and enhance parts of the structure to make modeling feasible. The NJF lifts that constraint. The system does not require onboard sensors or design adjustments to allow for control. Designers can explore unconventional and unconstrained forms without worrying whether they can model or control them later.

“Think about how you control your fingers. You sway, observe, and adapt,” says Li. “That’s what our system does. It experiments with random actions and knowing which controls move which parts of the robot.”

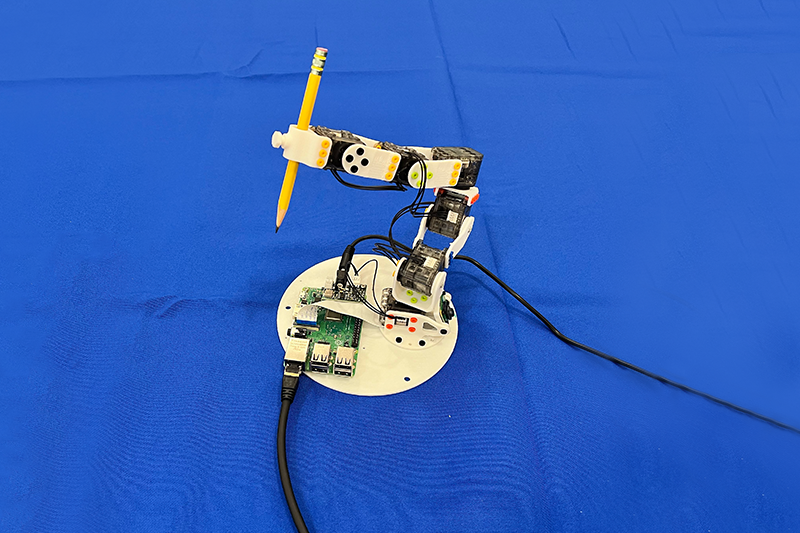

The system has proven to be robust across a variety of robot types. The team tested the NJF with pneumatic soft robotic hands that allow pinch and grind pins, rigid Allegro hands, 3D printed robotic arms, and even rotating platforms that do not have built-in sensors. In all cases, the system learned how it responded to the robot’s shape and control signals with just vision and random movement.

Researchers see possibilities that go far beyond the lab. NJF-equipped robots can one day perform agricultural tasks with centimeter-level localization accuracy, operate on construction sites without elaborate sensor arrays, or navigate dynamic environments where traditional methods break.

The NJF core has neural networks that capture two intertwined aspects of the robotic embodiment: three-dimensional geometry and sensitivity that controls the input. The system is based on Neural Radiation Fields (NERF), a technique that maps spatial coordinates to color and density values to reconstruct a 3D scene from an image. The NJF extends this approach by learning not only the shape of the robot, but also the Jacobi field. This is a function that predicts how the robot’s body points will move in response to motor commands.

To train the model, the robot performs random movements, with multiple cameras recording the results. No human supervision or prior knowledge of the robot structure is required. The system simply drives the relationship between control signals and movement by watching.

Once the training is complete, the robot only needs one monocular camera for real-time closed-loop control, and runs on approximately 12 HERTZs. This allows one to observe, plan, and act on itself continuously. This speed makes NJF more feasible than many physics-based simulators for soft robots.

In early simulations, even simple 2D fingers and sliders were able to learn this mapping using only a few examples. By modeling how a particular point transforms and shifts according to actions, the NJF constructs a dense map of controllability. This internal model allows generalization of the movement of the entire robot body, even when the data is noisy or incomplete.

“What’s really interesting is that the system has its own knowledge of which part of the robot controls,” says Li. “This is unprogrammed. It comes naturally through learning, like people discovering buttons on new devices.”

The future is soft

For decades, robotics have favored hard, easily modeled machines, like industrial weapons found in factories. However, this field is heading towards soft, bio-style robots that can adapt more fluidly to the real world. trade off? These robots are difficult to model.

“Robotics today are often out of reach due to costly sensors and complex programming. The goal at the Neural Jacobian Field is to lower the barriers, making robotics affordable, adaptable and accessible to more people. “It opens the door to robots that can operate in messy, unstructured environments, from farms to construction sites, without expensive infrastructure.”

“Vision alone can provide the cue needed to eliminate the need for GPS, external tracking systems, or complex onboard sensors. This opens the door to robust and adaptive underground movements indoors, without drones or underground maps. RUS, Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Director of CSAil. “By learning from visual feedback, these systems develop internal models of unique movement and dynamics, allowing for flexible, self-monitored operations where traditional localization methods fail.”

Training the NJF now requires multiple cameras and requires redoing for each robot, but researchers already imagine a more accessible version. In the future, enthusiasts will be able to record random movements of robots on their mobile phones, just like they would take a video of a rental car before driving, and will use that footage to create a control model.

The system is not yet generalized between different robots, lacking force and tactile sensing, limiting its effectiveness for contact-rich tasks. However, the team is looking for new ways to address these limitations. It expands the ability of models to improve generalization, handle occlusions, and infer across longer spatial and temporal fields.

“Just as humans have an intuitive understanding of how their bodies move and respond to commands, the NJF gives robots such embodied self-awareness through their vision alone,” says Li. “This understanding is the foundation of flexible manipulation and control in real-world environments. Essentially, our work reflects the broader trends of robotics: from manually programming detailed models to teaching robots through observation and interaction.”

This paper summarizes Sitzmann Lab’s computer vision and self-monitoring learning tasks, as well as RUS Lab’s soft robot expertise. Li, Sitzmann, and Rus co-authored papers with Csail Affiliates Annan Zhang SM ’22, a doctoral student in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS). Boyuan Chen, a doctoral student at EECS. Hannah Matusic, an undergraduate researcher in mechanical engineering. Chao Liu, postdoc at MIT’s Sensable City Lab.

This research was supported by the Solomon Buchsbaum Research Fund through the MIT Research Assistance Committee, the MIT Presidential Fellowship, the National Science Foundation, and the Gwange Institute for Science and Technology.